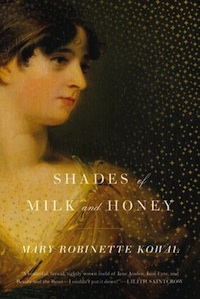

Mary Robinette Kowal’s Shades of Milk and Honey is a Regency Romance novel set in a Regency that’s just a shade off from ours. It’s a deliberately Austen-esque fantasy on a deliberately small scale. It’s England in the early Nineteenth Century, and accomplished young ladies practice piano playing, sketching, and glamour. Plain Jane has despaired of finding a husband while her beautiful younger sister is always surrounded by beaux. A stranger comes to the village and everything gets turned upside-down—but on the very smallest of scales. Reputations are theatened, but no worlds are at risk. And glamour is ubiquitous but generally insignificant, being used to make a room sweetly scented or have the sound of distant music playing.

If genres and subgenres are anything but marketing categories, they are a means of setting reader expectations. They’re a way of letting people know what they’re buying—all the semiotics of covers and type-styles subconsciously prime us for what shape of story to expect inside those covers, and also of the kind of pacing that story will have. I think in many ways pacing is genre, that there are different kinds of pacing for different genres, and although most readers couldn’t express this it’s what makes them find some books profoundly unsatisfying. It’s not just that if I’m reading a romance novel I expect that the book will end with the hero and heroine satisfyingly together and if I’m reading a mystery I expect that the crime will be solved. It’s a case of genre dictating where the beats will fall, where we can expect there to be climaxes and twists and what sort of description and worldbuilding there will be. When things violate these expectations it’s like stepping off a step that isn’t there. Science fiction can tell any shape of story—but a cover with exploding spaceships sets up expectations of pacing and resolution while distant pastel towers set up different ones.

Shades of Milk and Honey is much more like a Regency Romance in terms of scope and satisfaction than it is like what we normally expect of fantasy. The thing to which it is closest is Patricia Wrede and Caroline Stevermer’s Sorcery and Cecelia series, and looking at them together really highlights the differences. It’s not just that Kowal’s work has nothing like as much magic, it has nothing like as much peril either. Wrede and Stevermer have enemies for their protagonists to overcome, as well as heroes for them to kiss. Kowal’s heroine faces the kind of problems Jane Austen heroines have—lack of looks, lack of money, illness, elopements, fortune hunters, and fear of social embarrassment. If you go into it with expectations derived from fantasy you may find yourself wrongfooted.

The worldbuilding too is kept in the background of the story. The things we see glamour do could change the world more than they have—I can think of a lot of things that could be done with long term fixed illusions beyond decorating dining rooms, and cold-mongering ought to revolutionise food production and food safety in the same way refrigeration did in our world. As for bubbles of invisibility—the possibilities for spying are endless. This isn’t where Kowal wants to focus, and it isn’t what the book is about, in the way it would be in a more conventional fantasy.

Kowal clearly knows her Austen very well and tells a new story in Austen’s style. It isn’t Sense and Sensibility With Glamour. Of course, this is a twenty-first century novel, not a nineteenth century one. This is reflected occasionally in the language—Kowal does very well, but Austen’s heroines did not “feel fine” in the modern sense of the word—and consistently in the background axioms of what is important. Of course Jane finds love and economic safety, that she finds artistic fulfillment too is very much modern. I have no problem with this, indeed, I find it an improvement.

Shades of Milk and Honey was nominated for a Nebula last year, presumably because SFWA members noticed that it was well written and refreshingly different. While the pacing and the expectations are much more than of an Austen novel, this is definitely nevertheless fantas. Kowal is an accomplished writer of fantasy and science fiction and she knows how to use incluing seamlessly to let us know how the magic works, to weave it as lightly through the story as the web of honeysuckle scent Jane weaves through the drawing room. The glamour is an indispensible part of the story, which explains and encompasses it without ever slowing down. This is a smooth and beautifully written book that’s surprising as much for what it doesn’t do as what it does. There’s a lot of fantasy doing very standard fantasy things, it’s cool to see something taking the techniques of fantasy and using them to focus elsewhere.

I was impressed the first time I read it, but I enjoyed it a great deal more on re-reading when I already knew what I was getting. The sequel, Glamour in Glass will be out next Tuesday. (You can read an excerpt on Tor.com here.) I’m very interested to see where she takes it.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and nine novels, most recently Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.